During the last ten years, I have changed fields multiple times. From amateur photographer and through being a trained programmer, I am currently a student of political economy. Through these transformations, I have consistently obsessed with the tools I draw on to become better at whatever I’m focused on doing. Sure, no amount of sophisticated tooling will make the work produced by those untrained match the work of the most skilful. This goes without saying, any kind of expert is more than just the sum of the tools they master, but they can only go as high as permitted by the tools they use.

During my masters, which I have not yet finished, I have improved my tools for studying by leaps and bounds. Considering that I started taking notes with pen and paper, it has been quite the journey. I’m sure I’m yet to arrive at my final destination, as I will continue to discover new systems every day. Still, I’m currently at a checkpoint I’m proud of and that I consider worthy of sharing.

Personal Knowledge Management

The main problem behind studying is having to recall a significant amount of precise information from myriad sources that our human brains struggle to hold uncorrupted and whole. This is the problem that the study of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) is trying to address, which is in itself a part of the Information Sciences. This is a fascinating field of research that can be traced back to the commonplace books of the Renaissance. Today, people have their own personal wikis. As technology advances, I expect there to be further intuitive ways to manage our own personal and qualitative data.

A commonplace book from the mid-17th century.

Most of us that recognise this problem of dealing with textual complexity will initially call the solution ‘note-taking’. While note-taking addresses the collection problem, it ignores the other half of the equation: leveraging on your notes. I have been guilty of merely writing down ideas in a notebook to never see them again. With such a system, I’d often be aware that I had already written a note about a given topic, but consequently, become too demotivated to search for it. The sheer size of the paper pile made any writing task daunting. Even if we are to solve this problem of quick referencing using digital note-taking applications, the issue becomes into one of ambiguity. You will recognise this if, when reading your own notes, you often ask yourself “What did I mean by this? What was I doing when I wrote this down?”. These are questions that we can face very often when not taking notes carefully.

I like to think of my notes as processed knowledge. It’s essential to focus on the meaning of ‘processed’ here. It implies that my notes represent everything that I have consumed in a simplified and personalised form. The idea is to reduce the amount of effort it takes to reload the relevant insight. If I don’t take notes mindfully and phrase concepts in my own terms, then the amount of energy required to remember a given topic can be the same I spent reading the original text. Even worse, the required energy can be higher if I have to spend time searching or interpreting a note.

Building a Second Brain

My initial improvements from rudimentary note-taking came when I learned about the idea of Building a Second Brain, which is Tiago Forte’s name for the methodology he designed that is meant to help us manage our digital information. He divides the process into four stages.

Collect

As the name suggests, we need to make a conscious effort to collect everything that resonates with us and store it somewhere accessible and reliable.

Organise

In my experience, the most challenging part has been this one. Finding a digital place for every single idea can be time-consuming and makes me just want to pile nuggets of thought into a giant page and then retrieve them using a search function. However, this would come at the expense of discoverability which is important for when trying to make connections between ideas. Forte offers us the PARA method, which I still use partially, and provides a structure so that anything we think about has a digital space it belongs to. I will not go much into it however I do recommend reading more about it if you are the kind of person that can’t see their own wallpaper because of the sheer amount of files that are sitting in their computer desktop.

Distil

As I mentioned above, managing knowledge is not just a matter of hoarding, whether it’s organised or not. We want to be able to understand complex ideas as quickly as possible, especially given that we have already invested time into understanding those concepts before.

Express

Forte will tell you that all of the above is useless if we don’t share it with the world. This is not necessarily true, it is OK to collect information for our own selfish purposes.

All of the tools and methodologies I use fit into one of these four categories, which is why I consider it a very apt description of the cycle of activities we follow as knowledge workers. However, the methodologies I practice do not precisely replicate Forte. Before I actually start talking about tools, I will discuss my main point of departure from Forte’s Second Brain framework.

Luhmann’s Zettlekasten

Tiago Forte’s primary method for distilling information is what he calls Progressive Summarisation. Accordingly, when he goes over every text multiple times, every time highlighting a subsection of a previous until it is possible to read the whole text by a few selected key phrases. Besides being unable to afford to go over the most texts multiple times, it is a form of passive reading. These issues weren’t too glaring to me until I heard about Niklas Luhmann’s Zettlekasten method.

Luhmann was a prolific german sociologist that credited the fact that he was able to consistently pour out an enormous amount of work every year to his “slip box” or Zettlekasten. It essentially consists of just a bunch of flashcard sized notes in a card box with the catch that they’re all uniquely identified by a code. Luhmann used these IDs to cite ideas from other cards, but most importantly, he made sure that when he created a reference, he wrote down the referrer ID in the referred card, thus producing bidirectional links between ideas. Think of how Wikipedia lets you visit connected topics by clicking on the linked page, but imagine being able to see all the other pages that mention the page you’re reading, you’d be able to put the concept within context.

The Zettlekasten method has two main powerful implications. The first one is that there is a constraint in the size of the notes, therefore, forcing us to be extra mindful about what we write. When we make our notes truly concise, they behave as atoms that cannot be divided. When they are adequately bounded, they can be referred to without drawing on extra unnecessary information. This means they can be treated as bricks to build more complex ideas.

I have started to see some people fashion this method into powerful concepts. For example, Andy Matuschak uses finely scoped “Evergreen Notes” to build what he calls his Digital Garden. Elizabeth Van Nostrand conducts research by running what she has termed Epistemic Spot Checks, a comprehensive method whereby she rigorously sections her syntopical readings into claims and uses them to synthesise arguments that answer the questions she’s researching. A group of researchers in Human-Computer Interaction have started thinking about software that, Zotero, which focuses on papers as units, helps us collect grounded claims, they call it Knowledge Compressors.

The second salient benefit of the Zettlekasten method is that by referencing other ideas (and updating the back-references), we construct a network of our notes. On the other hand, the PARA method mentioned above is not a graph, it is only a tree. We do not actually put concepts together in trees. A more representative our brains would be networks, having an idea can trigger multiple connections to different concepts. Therefore, by storing information in an interconnected manner, every note will have extra context. We can also use this to our advantage when we wish to find new angles for an old topic, as with a network we can now browse around by clicking on links to lose ourselves in our notes.

Roam Research

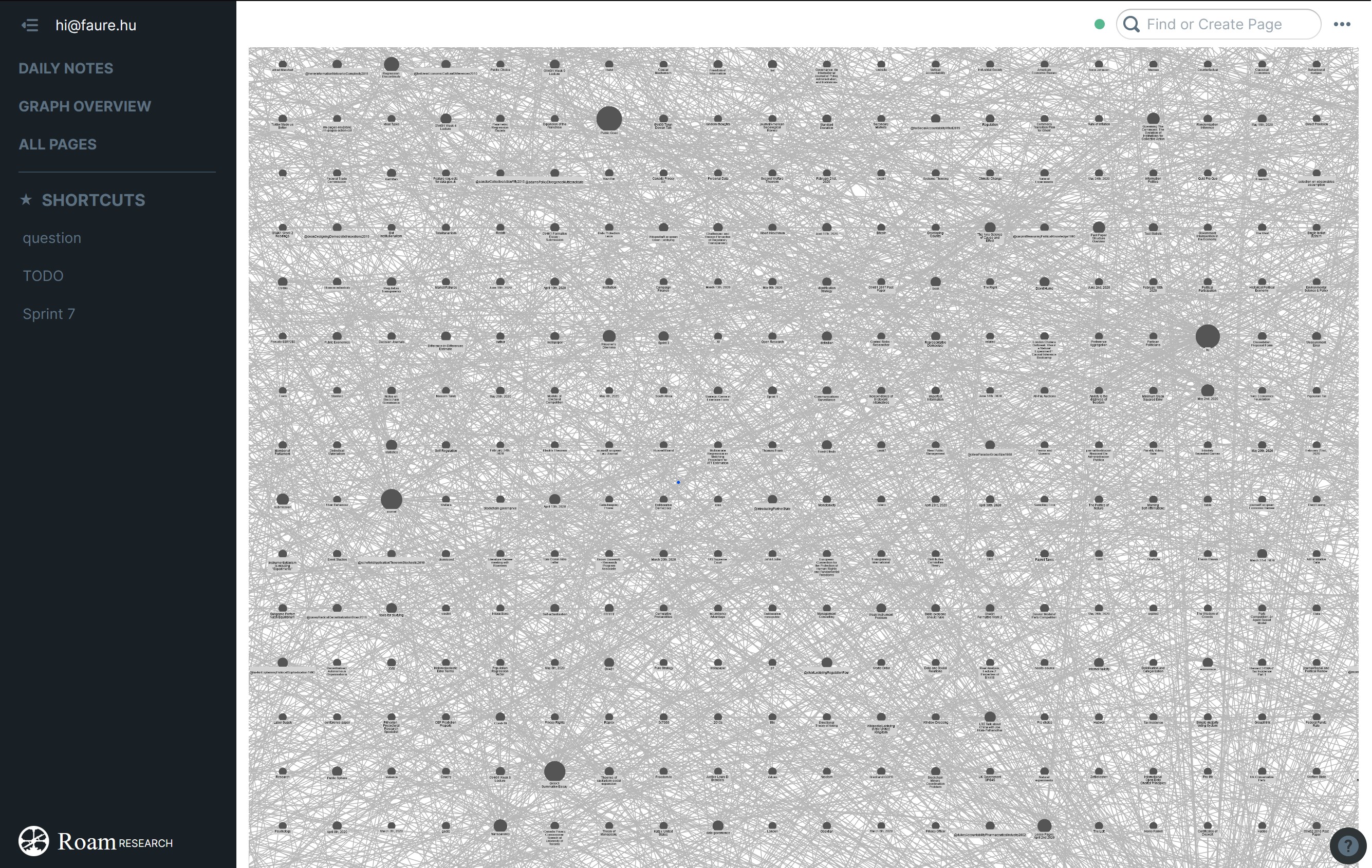

The first piece of software I want to bring up is the centrepiece of my personal knowledge management system, and it is Roam Research. Unlike with most note-taking applications like Evernote and OneNote, I can create links within pages, it is more like Notion in that regard. However, it also has backlinks. Meaning that, for every page, I can also see what other pages are referencing it. As mentioned above, this is very helpful to be aware of connections. It even provides graph visualisations to see what is the shape of your second brain.

Granted, I’ve been using Roam for almost half a year now, so I must have over a thousand of entries which makes my graph very dense to read and not particularly useful. It must be said that the development of the application is still in the early days, and there is plenty of room for improvement. For the time being, I can see local graphs for each page, so that every connection is visualised.

My personal knowledge graph.

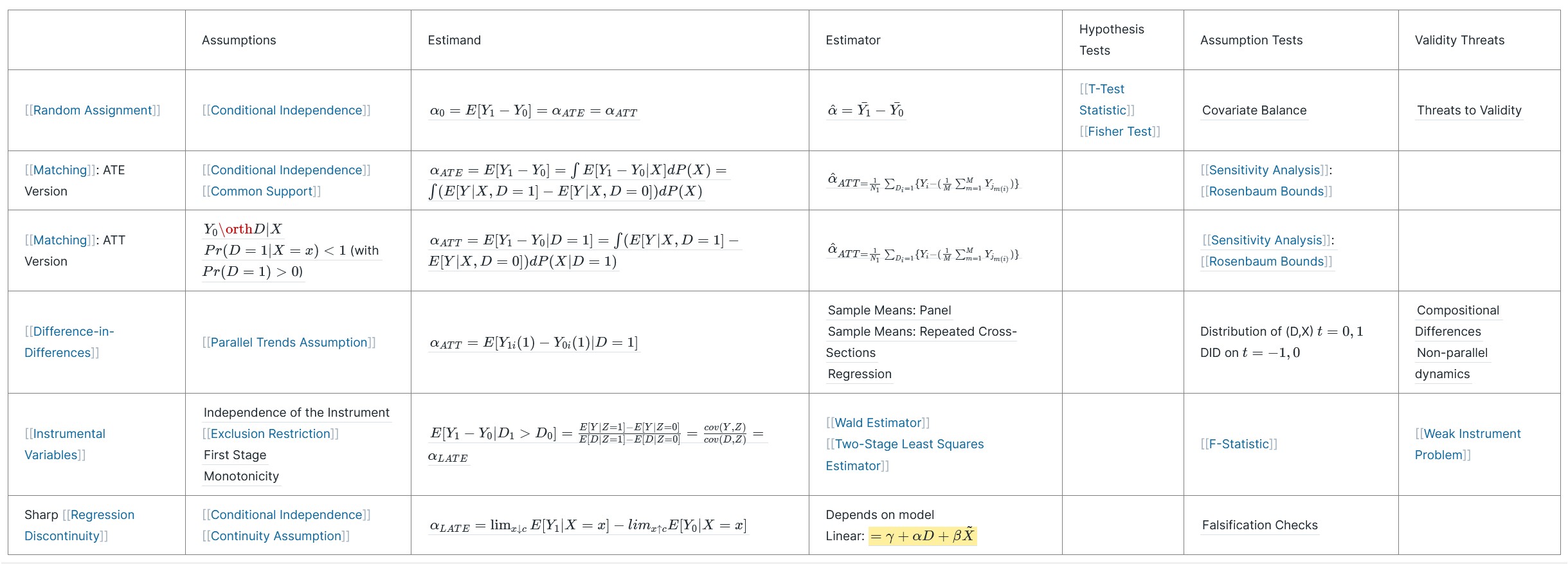

Bidirectional links are incredibly beneficial but not even my favourite feature of Roam. A lot of people start using Roam for the graph and bidirectional links, but other applications can do that just as well. The reason to stay with Roam, even with all their beta bugs, is that its the only app that has text transclusion, enabled by block references. In addition to making references to other parts of my knowledge base, block references allow me to pull the content from its source and make it part of a new idea. Thus a statement can be said once but used multiple times in different contexts, never repeating myself. I use block references for more than just deriving complex ideas from tinier blocks, but also to remix the same items with new structures. An example of this is the cheatsheet I made for reviewing a course where we learned variations of the same basic concept, each of which had its own page. Having recognised that a table would be ideal for enabling an overview, I constructed one with block references where clicking on each item leads me to the source.

A table with block references.

In fact, many people in the Roam community were raving about bidirectional links without giving enough consideration to the block references that I decided to make a quick video showcasing their usefulness.

As the name implies, block references are references of, duh, blocks. Blocks are the principal unit in Roam, which means that all text is organised in blocks. Another advantage besides references is that Roam can provide a scratchpad. I like to think of it as a tray where I load only relevant ideas I collect as I browse around the knowledge base. When it’s ready, the scratchpad sits in the sidebar giving me suggestions as I write in a blank page.

Another feature that might seem irrelevant at first sight but then turns out to be the main instigator of a note-taking philosophy is the Daily Notes. In Roam, the home view is always a note of the current date. Every day it automatically creates a new page where you can just dump ideas without having to stress about finding a place for it. Personally, it was quite meaningful. When I was using other note-taking applications such as Notion where I did not have the support of a graph, if I did not place an idea in a place designed for it, then it would quickly get lost. I started using an inbox so that everything I came up with I dumped into it, and by the end of the week, I sorted the accumulated pile in the inbox. This became unmanageable quickly. Roam’s network form allows me to just write jot down my thoughts on whatever page I am focused on and trust my links to create the connections that will make my ideas surface when they’re useful. Daily notes are a consistent reminder of this organisational philosophy. In my experience, one less bit of friction makes it easier to just pour out your thoughts, which is followed by an increase in productivity.

As I already mentioned, Roam is in a beta stage, meaning that it is still buggy and has a lot of pending features. It does not have a mobile application yet, and some buttons feel icky. However, the features it currently has is evidence that the team has a strong vision for what a powerful tool for thought can be.

Annotations

Perhaps the whole preamble to Roam was just so that when I started talking about Roam, it was already apparent how powerful their features are. However, Building a Second Brain is more than just organising. With regards to collecting information, most of the time, I just type down into Roam. The rest of the time, I will use tools to capture content from all over the place.

I want to be careful here and avoid recommending that you do all of your reading with a highlighting mentality. Active reading is more than just noticing which passages are more important than others, and we should try to make notes that put in our words what the author is trying to communicate. This will test our understanding. I also recently started discovering the added benefit that if we are guided by our notes, then we need not read a text in a strictly linear order. We can jump around the page looking for hints of those substantial portions that will complete our notes.

When I am reading more passively, I will use Hypothes.is and Instapaper interchangeably. Both tools let me take any webpage from the internet and highlight or write comments on specific passages of text. When I want to export highlights from books, I will simply transcribe by hand if it’s a physical book. If it’s a digital copy I read on my Kindle, then I have been using Readwise to extract my annotations into markdown form, which are fitting to paste into Roam.

When it comes to journal articles, I most often prefer to print them because, for some reason, it’s much more comfortable for me to read them that way. I use a highlighter, and when I am done, I use any PDF to replicate the highlights. I am then able to automatically extract these digital highlights into text form to paste into Roam, thanks to Zotero and its Zotfile plugin.

Reference Management

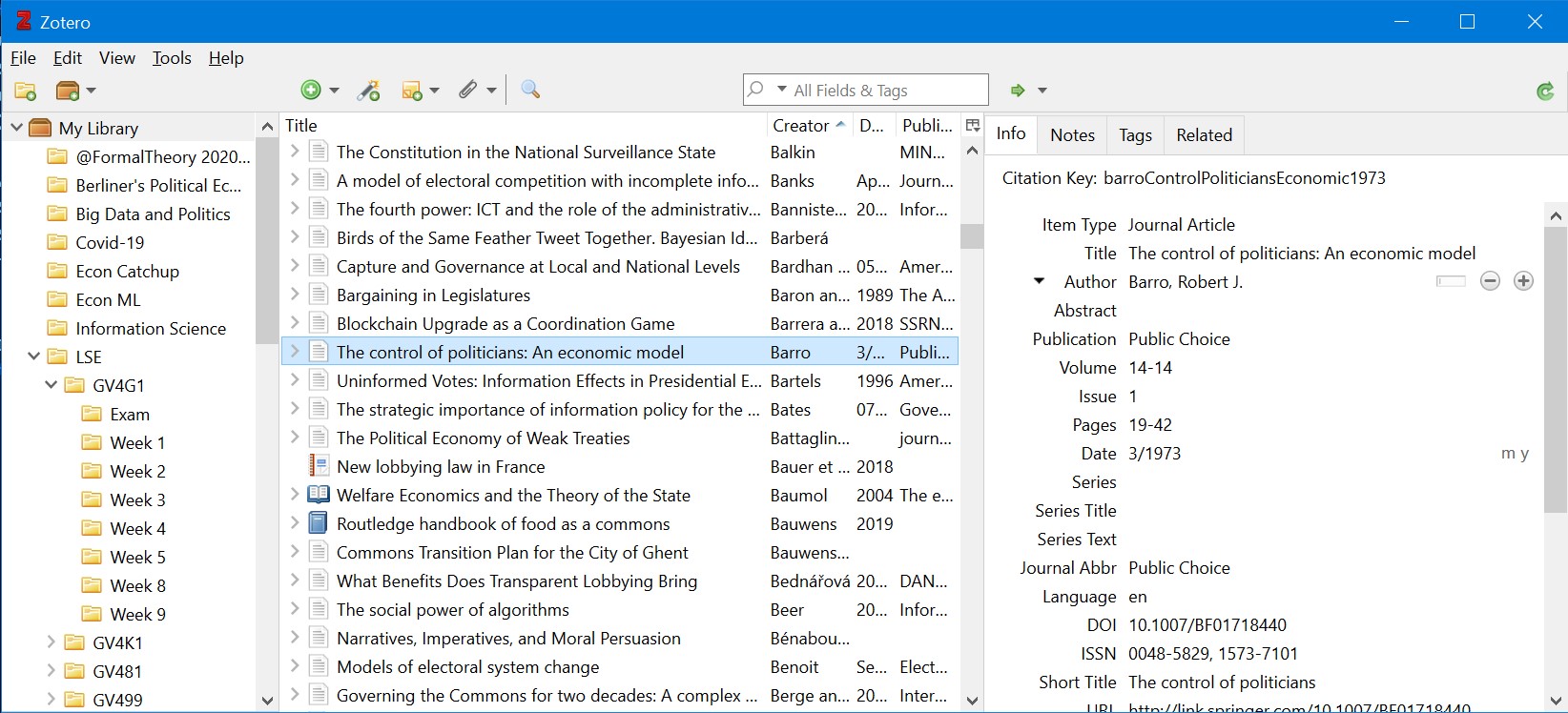

At the graduate level, most of the readings are in the form of academic journal articles. Starting with merely saving these PDF files in the directories I had for each course was straightforward. However, without a reference manager, the bibliography section of any paper is painful to put together. Enter Zotero, where I organise all of my readings.

Besides creating bibliographies, Zotero plugins help with some extra work. As I mentioned above, the Zotfile plugin lets me extract the highlighted text from my PDFs so that I can paste it into Roam. The pasted text will include links to the PDF file, specific to the page, which allows me to summon the PDF reader within Roam. It will go directly to the quoted passage and its context.

Zotero has a browser extension that lets me easily capture papers from the web. If there’s an article I want to add to my collection, I just need to go to the publisher’s site of the paper and press the extension button to fetch the PDF and download it into my computer. All the documents I download into my computer are also automatically copied into the cloud thanks to Dropbox. This lets me read and highlight papers on the go with the PDF reader on my phone.

If I can’t find a paper online or if I don’t have access to it, I just need to find the DOI and thanks to the Scihub Zotero extension I can just paste the DOI and Zotero will find it for me and then download it. If I am reading a paper and I want to get a cited article, I usually just need to find its DOI in the bibliography, which I then paste into Zotero and it automatically makes it available for me.

Better BibTex (BBT) for Zotero generates a unique citekey for every item. I then use these citekeys everywhere I cite the paper. In Roam, for example, my pages have titles like @bradyChallengeBigData2019. This is just for organisational purposes, but the magic happens when using it in a Latex processor. If you add the code generated by BBT to your Latex document, every instance of the citekey will be automatically converted to the citation in the style you desire. For example, (@bradyChallengeBigData2019) will turn into (Brady, 2019).

Expressing Your Ideas

Part of my switching to a social sciences programme is because I wanted to understand how to make better arguments about social behaviour and be really good at communicating them. One year back at university won’t be nearly enough, but the progress I have made has been gratifying. A significant factor has been the fact that I’ve focused on building a reliable knowledge base. The capacity to readily back my claims with sourced evidence gives me the confidence to express my ideas.

I already stated that I don’t think PKM systems are about expressing your thoughts, but as a student, you most probably will have to demonstrate your knowledge in essay form. Essay writing can be excruciating if you don’t follow good practices, and it can also be daunting to face a fresh white page. For the former problem, no tool is going to replace your capacity to collect your thoughts through the use of mindmaps, brainstorming, outlining, or whatever makes you conceive the backbone of your argument.

For the common problem of mental blocks, I like to use The Most Dangerous Writing App. This simple tool is useful for when you’ve already been blanking for too long and will be content with just producing the roughest possible draft. TMDWA will start a timer as you begin typing, every time you stop typing, it will start fading the work you have done so far. Idling for too long will make your work disappear. Vertigo produced by this threat will make your sentences less coherent as you get closer to the time limit, but it will also force you to pour out everything you have in your mind without any other preoccupations. I like doing 10-minute sprints.

I use Scrivener for writing. I do not necessarily consider it to be a game-changer, but it’s been useful for dividing work into sections and focusing solely on them individually. As with Roam, Scrivener lets me change the order of sections and hide them from the final export if I get past over my word count.

Conclusion

That concludes my overview of essential tools for studying. I hope this has been useful for you, and it provides ideas for your journey towards finding the stack that best suits you. If there’s anything that you think I could be doing better, please let me know! I’m happy to take suggestions. If you’re reading this as you start a new academic year, I wish you the best!